9 Musical Score

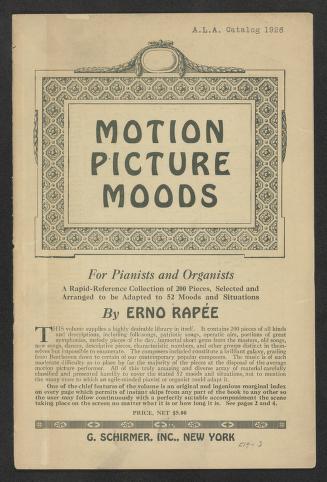

As we noted in the previous chapter, before sound synchronization a musician (or musicians) often improvised music along with a film.[1] These improvisations might have been entirely new music, or the musical selections might have been drawn from preexisting pieces. In the early 1920s, some enterprising folks like Erno Rapée published collections of music for cinema pianists. His Motion Picture Moods (1924) was a valuable resource for a solo musician who wanted a quick and easy way to sight-read music that had been categorized into “fifty-two moods and situations,” according to the title page. Some of these moods and situations included: “battle,” “gruesome,” “Misterioso,” and “sadness,” and included a host of dance forms and national songs (organized by nation or ethnic group). It had the added benefit of being a “Rapid-Reference” collection, and this was achieved by a handy list on the outer margin of each page, which would quickly send you to the next mood or situation you needed to accompany.

Motion Picture Moods

Before the technology existed to encode a musical track onto the actual film, there were attempts to sync up sound and visuals. Thomas Edison’s Kinetophone was an early experiment in linking up sound and picture, but it was designed for a single viewer. The next Edison system took the process a step further. In 1926, Western Electric used an Edison patent for its Vitaphone system (see Chapter 8 for more information on the Vitascope), which paired up sound recorded on a phonograph record with projected visual images. Each reel was designed to be the length of one side of a record.

Vitaphone System

As discussed in the previous chapter, the late 1920s saw the emergence of technology that led to synchronized soundtracks. Scholars of film sound now focus mainly on three sonic elements: dialogue (speech), sound effects (including ambient noise), and music. In his discussion on the role of sound in film, James Buhler states, “the soundtrack shapes or interprets the image track for us: It encourages us to look at the images in a certain way, to notice particular things, and to remember them.” Just as the director chooses camera angles and shots that bring certain characters to the forefront or draw your attention to what’s happening in the background, sound can function similarly. The sound mixing may foreground dialogue in one scene, while in another background character chatter is seen but not heard as music or sound effects become more noticeable. Sound, like visual sets and costumes, forms an element of continuity.

Early Characteristics of Film Scores

As sound film took hold and the technology for recording (on-set) and reproducing sound (in theaters) became more refined, certain practices came to be expected from the film-viewing experience. According to Roger Hickman, some general characteristics of film music were established:

- Extensive use of music (often referred to as “wall-to-wall” music)

- Exploitation of the full range of orchestral colors

- Reliance on the melody-dominated style of the late nineteenth century

- Frequent borrowing of familiar melodies

- Musical support for dramatic moods, settings, characters, and action

- Unity through leitmotifs and thematic transformation (12)

Once principal shooting of a film wraps up, the film then gets edited into what’s called a “rough cut.” This cut is often accompanied by some preexisting music. This is called a “temp track.” The music on the temp track may be made up of songs, classical pieces, or other film music. When a piece of music is chosen for the temp track, it can be because the director wants this specific piece (which the music supervisor then must purchase the rights to) or it could be that they just want new music that “sounds like” the chosen piece. The director may want the composer to capture a specific mood, an overall tone, or a tempo, or the director may want to mimic the instrumentation, the melody, or some other quality in the music.

The temp track also hints to another crucial piece of information: where the director wants music. Depending on the director (and, more important, on the collaboration between composer and director), this aspect might be part of a larger discussion. There is also usually something called a “spotting session,” which is an opportunity for the director and composer to watch a film together and talk about where musical cues or silence will go. Now, this is an extreme simplification of the process because the director and composer might each have their own philosophy of how music should function in a film, and there are many different ways to score a film or a scene. We’ll break down a couple of the most famous collaborations to see how certain directors and composers work together.

Composers nowadays might score the whole film in a DAW (digital audio workstation) or use notation software to complete written scores and create parts for the musicians. In the pre-digital era, composers wrote ideas on paper for orchestrators to turn into full scores (John Williams still works this way, but he’s in his 90s). If there are many musicians hired to complete the score, there will likely be recording sessions where the composer (or assistant) will conduct the ensemble to fit to a more finely tuned edit of the film.

In addition to music, sound effects, foley, and ADR (automated dialogue replacement) are added in postproduction and mixed by a sound mixer. If you’re at all interested in sound mixing, we recommend a documentary called Making Waves (2019.)

Trailer for Making Waves

Music Supervisors

In addition to a newly written score, sometimes films use preexisting songs. Some screenwriters and directors write their movies with particular songs in mind. Quentin Tarantino, for example, has explained that he writes his movies while listening to selections from his own album collection. Those songs can then be woven into the film because someone in production handles getting the legal rights to play them in the movie. Depending on the song, the license to play a song in a film generally costs between $20,000 and $45,000, with some running up to $60,000. Sometimes directors will cut corners somewhere else in the film so they can get the exact recording they want for a scene. This is especially true on lower budget films.

Tarantino on music in film

Many times, though, a Music Supervisor will suggest songs or musical pieces for a particular place in a film. Broadly speaking, the Music Supervisor–whether working in film, tv, advertising, video game, etc.–is the person who combines music and visuals. The Guild of Music Supervisors’ website defines the job as being for “A qualified professional who oversees all music related aspects of film, television, advertising, video games and any other existing or emerging visual media platforms as required.”[2]

“Throughout its long association with film, music has been used to manipulate the spectator, to explicate the internal, and to fill in the blanks of the missing psychological and emotional pieces of a narrative and the mise-en-scène. Indeed, music is important to film both because of its ability to enhance the listener’s experience of the film, to suture them into it if you will, but also to cover sloppy editing or fix a scene that simply does not work. –Gregg Redner (4)

Diegetic and Non-Diegetic Redux

As the use of sound in cinema has become more and more sophisticated over the last century, music has remained central to how filmmakers communicate effectively (and sometimes not so effectively) with an audience.[3] At its best, music can draw us into a cinematic experience, immersing us in a series of authentic, emotional moments. At its worst, it can ruin the experience altogether, telling us how to feel from scene to scene with an annoying persistence and obviousness.

Recall the distinction between diegetic and non-diegetic sound from the previous chapter. Film scores are always non-diegetic: the characters cannot “hear” the music. In contrast, a song on a soundtrack might be diegetic if the character listens to it on screen. Thus, non-diegetic music communicates only to the audience, while diegetic music communicates both to the characters on screen and the audience. Think about the movie Jaws (1975). Even if you haven’t seen it, you probably know those two, deep notes – da dum… da dum – that start out slowly then build and build, letting us know the shark is about to attack. Meanwhile, the kids in the water are listening to pop music, completely oblivious to the fact that one of them is about to be eaten alive! See 1:32 and following below:

Jaws

This concept applies to more than just music. Titles, for example, are a non-diegetic element of mise-en-scène. The audience can see them, but the characters usually can’t.[4]

The most widespread function of film sound consists of unifying or binding together the flow of images separated by cuts. In temporal terms, it unifies by bridging the visual breaks through sound overlaps. In spatial terms, it unifies by establishing atmospheres (bridsongs, traffic sounds) as a framework that seems to contain the image, a heard space in which the “seen” bathes. Third, sound can provide unity through non-diegetic music: because this music is independent of the notion of real time and space it can cast the images into a homogenizing flow.–Michel Chion (47)

Soundtrack

We also need to distinguish between a score written by a composer and a soundtrack of popular music (either original or preexisting) used throughout a motion picture.

A soundtrack is an audio recording created or used in film production or postproduction.[5] Initially, the dialogue, sound effects, and music in a film have their own separate tracks (dialogue track, sound effects track, and music track), and these are mixed together to make what is called the composite track, which is heard in the film. Late in the 1940s “sound track” became one word, “soundtrack.” A soundtrack comprised of preexisting songs (or soundtrack of original songs) became a way of advertising the movie.[6]

The use of popular music in film has a long history, and many of the early musicals in the 1930s, 40s, and 50s were designed around popular songs of the day.[7] As noted above, most contemporary films or television series have a Music Supervisor who is responsible for identifying and acquiring the rights for any popular or preexisting music the filmmakers want to use in the final edit. Sometimes those songs are diegetic – that is, they are played on screen for the characters to hear and respond to. At other times such songs are non-diegetic – that is, they are just for the audience to put us in a certain mood or frame of mind. Either way, they are almost always added in postproduction. Even if the music is meant to be diegetic, playing the actual song during filming would make editing between takes of dialogue nearly impossible. Instead, the actors pretend they are listening to the song in the scene.[8]

Here’s a scene from Melina Matsoukas’s Queen and Slim (2019) that employs a diegetic song:

Queen and Slim

Here’s a non-diegetic use of Marvin Gaye’s “I Heard It through the Grapevine” in The Big Chill (1983):

The Big Chill (see 1:01 and following)

A soundtrack that employs preexisting songs can quickly establish a number of effects such as:

- Connecting with the audience: a popular or iconic song can engage viewers by tapping into shared cultural experiences and references.

- Establishing a film’s temporal setting: older songs can help evoke a historical era. A well-chosen song can quickly transport the audience to a prior time or different cultural setting, enhancing the film’s authenticity and immersive quality. Here are the opening credits from American Graffiti (1973), which use “Rock Around the Clock” to clue the viewers that they are watching a film set in the 1950s:

American Graffiti

- Enhancing theme: songs with relevant lyrics or tones can underscore a film’s ideas. The right song can amplify the narrative’s emotional or thematic elements, providing depth and nuance to the storytelling. In the following scene from Easy Rider (1969), “Born to Be Wild” underscores the film’s subversion of societal norms:

Easy Rider

- Character development: music can reveal a character’s personality, tastes, or emotional state. A character’s choice of music, whether they are listening to it diegetically or it is used in association with them, can provide insights into their identity and motivations.

- Building mood and tension: The rhythm and energy of a song can enhance a film’s atmosphere or build suspense. Upbeat tracks can create a lively atmosphere, while slower or more dramatic songs can heighten anxiety or anticipation

- Generating irony: the unexpected use of a popular song can be jarring to the audience and create a disconnect between the tone or lyrics of the song and the events shown on the screen. The use of the upbeat “Good Vibrations” during a murder scene from Jordan Peele’s Us (2019) provides a textbook example:

Us

Of course, some directors will overrely on popular music to mask weak scripts, subpar acting, and other deficiencies. In the postproduction process, directors and editors might try to “paper over” holes by inserting energetic or emotionally poignant songs that can help distract the audience. For instance, many of Elvis Presley’s films were little more than flimsy excuses for him to sing occasionally. More recent examples where the music exceeds its source include Space Jam: A New Legacy (2021) and Twilight Saga: New Moon (2009).

Score

The type of music that gets the most attention in formal analysis is the score, the original composition written and recorded for a specific motion picture.[9] A film score, unlike popular music, is always non-diegetic. It’s just for us in the audience. If the kids in the water could hear the theme from Jaws they’d get out of the water and we wouldn’t have a movie to watch. The score is also typically recorded after the final edit of the picture is complete. That’s because the score must be timed to the rhythm of the finished film, each note tied to a moment on screen to achieve the desired effect. Changes in the edit will require changes in the score to match.

Meanwhile Podcast on film scores

It is in the score that a film can take full advantage of music’s expressive, emotional range. It’s also, however, where filmmakers can go terribly wrong. Music in film should be co-expressive with the moving image, working in concert to tell the story. The most forgettable scores simply mirror the action on screen instead of adding another dimension. What we see is what we hear. Far worse is a score that does little more than tell us what to feel and when to feel it: the musical equivalent of a big APPLAUSE sign.

These tendencies in cinematic music are what led philosopher and music critic Theodor Adorno to complain that the standard approach to film scores was to simply “interpret the meaning of the action for the less intelligent members of the audience” (60). Ouch. In a way, he’s not wrong, although not about the audience’s intelligence. He may have a point, however, about how filmmakers assume a lack of intelligence on the part of the spectator–or at least assume a lack of awareness of the power of music in cinema. Take the Marvel Cinematic Universe for example. Most of you know the theme to Jaws. You probably also know the musical theme for Star Wars (1977), Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), and maybe even Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (2001). Can you, though, hum a single tune from any Marvel movie? Weird, right? Check this out:

The Marvel symphonic universe

The best cinema scores can do so much more than simply mirror the action or tell us how to feel. They can set a tone, play with tempo, subvert expectations. Music designed for cinema with the same care and thematic awareness as the cinematography, mise-en-scène or editing, can transform our experience without us even realizing how and why it is happening.

Take composer Hans Zimmer for example. Zimmer has composed scores for more than 150 films, working with dozens of filmmakers. He understands how music can support and enhance a narrative theme, creating a cohesive whole. In his work with Christopher Nolan– The Dark Knight (2008), Inception (2010), Interstellar (2014), and others–his compositions explore the recurring theme of time:

Dan Golding on Hans Zimmer

Sometimes, as in the following scene from Moonlight (2016), a director will substitute the score for dialogue in a pivotal scene.

Moonlight

Underscore

James Wierzbicki explains that many films also employ an “underscore,” non-diegetic music that accompanies dialogue or even other sound effects (6). Underscores, sometimes called musical cues, tend to emphasize the emotional content of the dialogue or its attendant actions. Typically, the underscore is much less prominent than the main score and subtly guides the emotional response of the audience, providing what Wierzbicki refers to as “mood enhancing, action-illustrating, drama-propelling music” (7). Audiences are not meant to notice underscore at a conscious level.

Music Underscoring

Underscoring in Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003)

Leitmotif

Composers use recurring themes, or motifs, as a kind of signature (or even a brand) for a film or tv series. The most famous of these are the ones you can probably hum to yourself right now, again like Star Wars, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone.

Composers can use this same concept for a specific character as well, known as a leitmotif. A leitmotif is akin to “walk up music” for an athlete. Think of those two ominous notes we associate with the shark in Jaws. That’s a leitmotif. How about the triumphant horns we hear every time Indiana Jones shows up in Raiders of the Lost Ark? That’s a leitmotif.[10] Leitmotifs help an audience identify a character with a particular mood, but they can also function as a cohesive device irrespective of a character. Here’s a famous leitmotif associated with Harry Lime, a character from The Third Man (1949):

The Third Man

Here’s a scene from Australia (2008) that the film uses as a multicultural leitmotif for life and hope as well as allusions to both The Wizard of Oz and the indigenous Rainbow Serpent.

Australia

Special Functions of the Musical Score

The score can speak to a film viewer in many different ways.

- Heighten the Drama of a Scene

- Help to Tell an Inner Story

- Staying True to Time/Place

- Foreshadowing and/or Building Tension

- Adding Levels of Meaning to the Visuals

- Understanding a Character through Music

- Triggering a Conditioned Response

- Traveling Music

- Providing Transitions

- Setting the Tone of the Film

- Incorporating Sounds as Part of the Score

- Music as Interior Monologue

- Music as a Base for Choreographed Action

- Covering Weaknesses in the Film (Petrie and Boggs 265-278)

As you can see, the musical score can impact us and is a useful tool of the filmmaker to truly reinforce ideas within a film.

Silence

Ironically, the advent of sound technology also allowed for film to become truly silent for the first time.[11] Once audiences became accustomed to listening to sound – hearing it, differentiating its layers, interpreting it – the most radical way to get attention was to turn the sound off. In 1931, Fritz Lang’s M did just this. Contrasting boisterous musicals and chatty rom-coms, M turned to dark themes of child abduction and murder. When a little girl Elsie goes missing, Lang uses silence to show the gravity of her absence. We see shots of her empty chair at the dinner table, her ball rolling to nowhere, her balloon disappearing into the sky – all absolutely silent with no music or dialogue to ease the audience’s nerves or provide solace.

Silence can help create a number of effects, including suspense, a character’s sense of isolation, visual awe, or emotional impact.[12]

A Quiet Place (2018)

Stalker (1979)

The Assassin (2015)

Ikiru (1952)

Sometimes, a director will employ a dead track, an extreme type of silence, in which not even the slightest ambient sound is heard. Here’s an example from Munich (2005).

Munich (dead track around 30-second mark)

A note about sources

- https://oercommons.org/courseware/lesson/109868/overview ↵

- https://oercommons.org/courseware/lesson/109868/overview ↵

- https://uark.pressbooks.pub/movingpictures/chapter/sound/ ↵

- https://uark.pressbooks.pub/movingpictures/chapter/sound/ ↵

- https://milnepublishing.geneseo.edu/exploring-movie-construction-and-production/chapter/8-what-is-sound/ ↵

- https://milnepublishing.geneseo.edu/exploring-movie-construction-and-production/chapter/8-what-is-sound/ ↵

- https://uark.pressbooks.pub/movingpictures/chapter/sound/ ↵

- https://uark.pressbooks.pub/movingpictures/chapter/sound/ ↵

- https://uark.pressbooks.pub/movingpictures/chapter/sound/ ↵

- https://uark.pressbooks.pub/movingpictures/chapter/sound/ ↵

- https://pressbooks.cuny.edu/globalfilmtraditions/chapter/chapter-6-sound/ ↵

- https://pressbooks.cuny.edu/globalfilmtraditions/chapter/chapter-6-sound/ ↵