3 Fictional and Dramatic Elements of Film

THE CLASSIC HOLLYWOOD NARRATIVE FORM OF FILMMAKING

We understand that most films have only 90-120 minutes to tell a story that takes place over an often much longer period of time; how a film successfully does this involves the combination of a variety of techniques and conventions that help compress time, but it all begins with a well-constructed story that contains characters involved in situations that audiences want to relate to.[1]

Learning how to identify the structure of a film is different from just being able to recount what happens in the story. Most film narrative functions as a causal chain: one event or decision leads to another. Some films, however, attempt to undercut narrative convention and employ a more “random” or chaotic approach to telling a story that pushes against expectations of unity.

Most films, though, have a distinct beginning, middle, and end — or often what we can also term the set-up, conflict, and resolution of that conflict. Such stories generally rely on a cause-and-effect pattern to move the action along that will seem logical to the viewers. These films contain engaging clues that let you anticipate what will be happening next. Through the narrative structure, films will disseminate information from the overall story (all of the events that are told) and shape it into a plot (the order those events are conveyed in).

German Playwright Gustav Freytag developed his “Freytag’s Pyramid” that went a bit further and outlined a five-part dramatic structure: The Exposition, Rising Action, Climax, Falling Action, and Resolution. After an introduction, the story builds to the scene of greatest importance to the protagonist, where his or her life is either going to change for the better or the worse. This story plays out in the latter part of the film, eventually coming to the conclusion or resolution.

In classic Hollywood narrative filmmaking, the story is almost always told in chronological order. One common exception to this rule is the inclusion of flashbacks, which filmmakers may use to provide backstory or to suggest motivations for characters in the present situation. Less commonly, films might disrupt linear narrative via flashforwards, which project characters and events into the future.

Primarily, the focus of these films is on the main characters; the editing of the film is seamless (or “invisible”), in the sense that the film intentionally does not try to call attention to anything that would break the illusion that the audience is seeing something “real.”[2]

Because of this invisible editing, viewers are not always aware of how often a film employs temporal ellipses, gaps in action. For example, we might first see a character in bed staring at a brick of heroin that her friend told her to sell before going to work. The film next shows her walking to her desk at work. The character’s morning routine, including her drive to work and trip up the elevator, are all “silently” omitted from the movie. Films may, thus, use ellipsis to delete incidents that are not instrumental to the plot (do we need to see our character brush her teeth?) In this case, though, the ellipsis does more than simply cut out the “boring bits.” Another key use of ellipsis is to withhold information from the viewers to keep them in suspense: did the character sell the drugs or not? While some ellipses may be only a matter of seconds or minutes, others may cut out months or even years (sometimes providing a temporal marker such as “later that day” or “two months later.”) Alternatively, some films, such as Cleo from 5 to 7 (1962), Run Lola Run (1998), Before Sunset (2004), and Twelve Angry Men (1957), purport to tell their stories in real time or close to it.

The classical narrative style of filmmaking ruled during the era when studio production dominated Hollywood, from the 1920s to the 1960s; the simplicity of this style made it easier for films to be made much like cars on an assembly line.[3]

Successful films engage the audience in different ways. Sometimes the audience only knows what the characters know; sometimes the audience knows more.

Unrestricted narration is when the viewer knows more than the characters. A great example of this is The French Connection (1971), where the viewer knows more about the heroin dealers than the cops played by Gene Hackman and Roy Scheider.

Restricted narration is when the viewer’s understanding is limited to what characters know. A good example of this is Star Wars: Episode IV, a New Hope (1977); the viewer only learns that Luke’s father is Darth Vader when Luke himself discovers this truth.

Parallel Story Lines and How They Differ from Cross Cutting

There’s a great scene in the famous film High Noon (1952) where Marshal Kane is writing out his last will and testament in his office while the bad guys coming for him are getting off at the train station. This is a classic example of cross cutting – the two events are happening simultaneously, in different places, but the audience has been given an absolutely clear understanding of the connection between the two. This technique goes back to the earliest days of filmmaking and Life of an American Fireman (1903) when this silent film cut back and forth between a fire in an apartment building and the fire station that gets the call and has the firemen respond.

Clock Scene from High Noon

Annotated version of Life of an American Fireman

Cross Cutting is a structural device intended to create tension. Will Kane get his will written out before Frank Miller and his gang can walk from the train station to the town? Will the woman in the apartment survive until she can be rescued by the firemen?

Parallel storylines are different, because the audience does not know the connection between what is happening in the different scenes. A great example of this is in The French Connection (1971). The film starts off in Marseilles in Southern France; an undercover detective is following a man near the waterfront. Later this detective is gunned down in front of his apartment.

The film then cuts to a drug bust in Brooklyn, New York. Two undercover cops, one dressed as Santa Claus, chase down a drug dealer and beat him up to try and get some information out of him. We have absolutely no idea of how these scenes are connected until more than halfway through the film. The film keeps cutting back and forth between these different stories, which is why we call the technique a parallel storyline. It is also part of the construction of the narrative, and the audience assumes that the connection will eventually be explained.[4]

New York Times reviewer looks at The French Connection forty years later

The Three-Act Structure

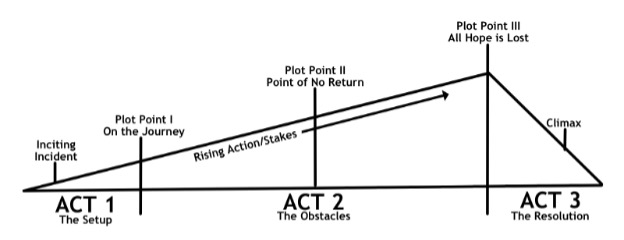

No matter what the genre, movie screenplays are typically written in a 3-act structure that roughly aligns with Freytag’s pyramid (discussed above.) We can see the exposition (set-up, inciting incident) in Act 1, the rising action (stakes, obstacles) in Act 2, and the climax, falling action, and resolution in Act 3.

Screenwriters generally employ this formula because of its simplicity and effectiveness. The structure helps to focus the audience’s attention and offer clarity to the film’s narrative, as each act performs a specific–and expected–function. It also generally helps the director establish narrative pacing designed to maintain audience interest. A film that “drags” in the middle likely extends the second act excessively, for example, while one that seems to end abruptly may not devote enough time to Act 3. Ideally, the three-act structure helps viewers identify the conflict, stay interested in its intensification, and cheer the aftermath.

In terms of character development, the three-act structure helps us “get to know” the protagonist and other key figures in Act 1, identify with the character’s increased tension in Act 2, and hope the hero earns a positive outcome in Act 3.

We can see the three-act structure on display in numerous films, including Casablanca (1941):

Act 1: The film establishes the primary setting (a bar in Casablanca) and the protagonist, Rick Blaine. It also introduces conflict in the form of Victor Lazlo, a key member of the anti-Nazi resistance, and his wife, Ilsa, who just happens to have had a previous relationship with … Rick.

Act 2: The action intensifies as Rick must choose between staying “neutral” and helping his ex’s lover avoid the authorities.

Act 3: Just when it seems all is lost, Rick shoots Major Strasser, a Nazi who attempts to thwart Victor and Ilsa’s escape. Victor and Ilsa escape, and Rick, no longer neutral or ambivalent, seems willing to continue helping the resistance.

Obviously, a lot more happens in the film, but by focusing on the three-act structure we can quickly discern how the film’s initiates its conflict, builds its tension, and resolves the climax.

Casablanca

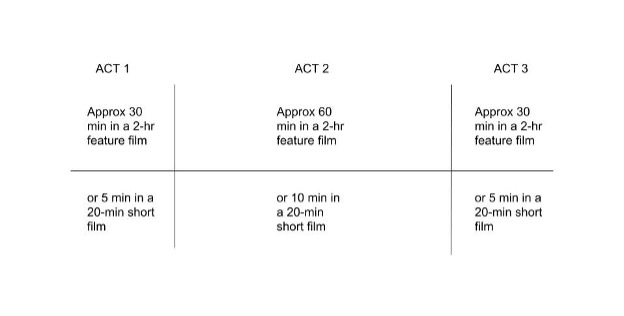

While many films contain three acts, those acts are rarely identical in length. Here is a common division for a two-hour movie:

Three-act division[8]

Lindsay Ellis explains how a three-act screenplay works in the following video:

To be clear, the three-act structure is not an explicit industry standard or a rule to which screenwriters must conform.[9] In fact, it is less a writing technique than it is an analytic tool, a way of breaking down cinematic stories for analysis. Unlike stage plays, there are no explicit act breaks in the script itself, and some writers actively work against the three-act structure in an effort to push beyond expectations in cinema. The films of Quentin Tarantino, for example, often “break the rules” for how cinema is supposed to work (and as a result his scripts often read more like novels than screenplays), but even Tarantino accepts the importance of setting up audience expectations and, eventually, paying them off. Even he understands that the journey of a protagonist toward their goal is littered with obstacles and follows an arc toward resolution. Another example of a film that toys with the three-act structure is Gina Prince-Bythwood’s Love and Basketball, which divides its action so that it mirrors four quarters in a basketball game. Another example of a film that challenges the three-act structure is Thirty Two Short Films about Glenn Gould (1993), which tells the life of its pianist subject via a series of vignettes that employ a variety of styles (including non-narrative techniques) and that subtly echo Beethoven’s 32 Variations in C Minor for Piano.

NON-LINEAR FILMMAKING

There is a strong tradition of narrative film—internationally and in the U.S.—that actively resists many of the patterns central to the three-act structure we have just described.[11] A narrative film in the Hollywood tradition can use this three-act structure because it follows certain features in its approach to narrative that are well adapted to it. For example, a commercial narrative film in the Hollywood tradition relies on a protagonist, one about whom the viewer is quickly educated in terms of their defining characteristics and their central problem, a problem that the long struggle of Act 2 will ultimately resolve in the descending action of Act 3.

In film that actively positions itself as an alternative to this tradition—including many international art house and independent films—we cannot necessarily count on a central consistent character single-mindedly dedicated to resolving a central problem, nor can we count on resolution itself. For example, the ending of The 400 Blows (1959) refuses the kind of ending—happy or sad—we have been trained by other films to expect. Instead, we end in a state of uncertainty as to the future of our protagonist, an uncertainty manifested on screen by the freeze-frame with which the film ends.

The 400 Blows, final scene

This refusal of the three-act structure’s promise of resolution does not, of course, mean the film has no structure. But it forces us out of the familiar patterns of genre and convention to attend to the structures of the film at hand. However, because of the dominance of the Hollywood tradition of narrative film, it is fair to say that much cinema in the world is thinking about these conventions, even if only to reject them, to position themselves against them. Thus, it can be helpful to compare an art film or independent film to those structures to see how it consciously refuses the expectations (as in the refusal of closure at the end of The 400 Blows). After all, three-act structure depends on certain conventions that define what is sometimes called “mainstream film.”[12]

For artistic reasons, some very successful directors have chosen to construct non-linear story lines for their films, including Orson Welles, Quentin Tarantino, and Christopher Nolan.[13] Non-linear means not in chronological order. It frankly can be very tricky in these films to keep the audience from being confused, but there are also many film enthusiasts that love films to challenge them in this way.

Pulp Fiction, Tarantino’s 1994 film, has three different stories that are told completely out of sequence. We start off at a scene in a diner where this strange couple is deciding to rob the place. We then cut to an earlier scene where two of the other diner patrons pay a visit to some low-level drug dealers who have ripped off their crime boss and end up whacking these unwary dealers. Another storyline involves an aging boxer who ticked off this same crime boss by not taking a dive in a big fight. At the end of the film, we are again back at the original diner scene, but this time seeing it from an entirely different point of view. It’s hard to describe how all of this works so well, but it does, and part of the appeal of this film is this unique story structure. Other famous non-linear films include Daughters of the Dust (1991), Citizen Kane (1941), Memento (2000), and Kill Bill: Parts I and II (2003/2004).[14]

In the following clip from Daughters of the Dust, we first see a character from the present, and then we hear a little girl from the future explain about ancestors from the past before ending with a different character from the present.

Daughters of the Dust

Summary of Narrative Structure

Outside of the characters, the narrative structure is the most essential part of a movie.[15] Narrative structure not only gives the framework for how a movie is told; it provides an avenue for the characters to grow. The narrative structure consists of the action being portrayed in chronological (linear) order or in a combination of flashbacks, flashforwards, and present time (nonlinear).

Narrative structure is a vicious cycle that begins with the plot telling the story how it is going to be told. The story goes through various changes from the exposition to the complication or conflict. As the protagonist or main character progresses through trying to resolve the complication, the protagonist moves the story along so we have rising action. The rising action comes to a climax where the protagonist has to make the ultimate decision of how to handle a situation to push it toward the end. After the climax, comes the falling action, because the main incident just occurred. At the end of the falling action, the viewer has arrived at the resolution/denouement, ending the movie.[16]

ART CINEMA

As indicated above, most mainstream–and even most independent–films employ some form of the classic three-act structure, although some directors of popular films undercut this approach with non-linear storytelling. David Bordwell, however, provided an influential theory about a method of filmmaking that explicitly subverts traditional narrative structure: art cinema. For Bordwell, art cinema strives for realism through psychologically complex characters and narrative ambiguity. Rather than moving from set up to obstacles to resolution as in a more traditional film, art cinema “ideally … hesitates, suggesting character subjectivity, life’s untidiness, and author’s vision” (60).

In “real life,” we often fail to receive a definitive resolution to our problems. Our perceptions of those resolutions can vary as well, both in the moment and subsequently. Art cinema leans into this indeterminacy, both in terms of plot and structure. While the classic narrative generally employs a clear cause-effect format wherein one action follows another in a causal chain, art cinema often adopts a more fragmentary, episodic form. Art films will often play with subjective notions of time. Complicating this further, Bordwell argues, is an idiosyncratic authorial voice, an “overriding intelligence” that serves as a type of meta-commentary on the film itself (59). Indeed, Bordwell claims that this voice can carry over from film to film, with certain “deviations” in style and theme serving as a type of signature. One might add that particular movements, such as the French New Wave, New Hollywood, and Dogme 95, also contain common elements that cut across individual films or oeuvres.

As a result, interpreting art cinema shifts much of the burden onto the viewer. Unlike a classic mainstream narrative, where most of the meaning is “spoon fed” to the audience through exposition and obvious visual connections, art cinema pushes against clear-cut interpretations.

Last Year in Marienbad (1961)

Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975)

Mother (2017)

What Makes a Story a “Good” Story?

When we look at characteristics of stories that are successful, they seem to have the following specific elements: the plot is well-structured, they are believable, they capture our interest, they blend simplicity with complexity, and they control our emotions effectively.[17]

Plot is Well-Structured: Within this idea, consider that every part of the story is serving a purpose. When you analyze this element, think about each section of the film and check to be sure that it was working to build the big picture of the storyline.

Believability: There are different ways to create believability. First, a filmmaker might try to create a story that shows the way things are in the real world. If so, they will try to include realistic portrayals of people and places so that you could envision the actions of the film happening in your real life. Or, a filmmaker might want to create a fictional “reality” where what happens is the way things are supposed to be in the world. Those are our “happily ever after films.” We like to buy in to them and believe them because we wish that was the way the world worked. Lastly, a filmmaker might use their artistry to show the way things have never been and will never be. Within this realm, whole new worlds can be created (think Edward Scissorhands [1990] The Matrix, [1999], Avatar [2009], etc.) that would never really exist, but if they are designed and produced effectively, the viewer sees them as believable for the duration of the film experience.

Capture our Interest: How can something be considered good if it’s not interesting? One goal of a good story is to hook our attention right away and then continue to captivate us as the story progresses. Sometimes a filmmaker will create interest through suspense. They will tease us with information and keep us wondering all the way until the end. Sometimes they kill off a popular actor early in the film to play with our minds. Or they might create surprise-endings that we never see coming. All of these are techniques that are used in storytelling to keep the level of interest high for the viewer from beginning to end.

Blend Simplicity with Complexity: Filmmakers only have about two-hours to fit everything in. Think about series that you watch on streaming services–their characters and plot lines can be intricately developed over multiple episodes and many seasons, but a film has to pack a punch in a very short time. The content has to be simple enough to be covered in a couple hours but complex enough that we are intrigued by what may happen. Trying to find the balance between both is difficult, but when it’s done well, the story hits the mark.

Control our Emotions Effectively: Maybe you are a viewer who likes a good cry every once in a while, but even if you are, you probably want a filmmaker to be careful with your emotions. Films that are overly sappy tend to annoy us–we don’t want things to feel too sentimental. And, we often develop feelings for characters as we watch films, so if we’re getting connected to them, we probably don’t want to feel their demise too harshly or see them die in graphic detail.

All of the above elements, if done well, lead to a quality storyline that does what it’s supposed to do and that leaves that viewer saying, “That was a good film.”[18]

NON-NARRATIVE FILM

While we have focused on movies that tell a story (linear or otherwise), some films dispense with narrative altogether. Non-narrative films employ visuals and sounds in a way that is unanchored from character and plot. Such films often generate an audio-visual mood, rhythm, or texture for the audience to engage with in a subjective way.

Typically associated with experimental cinema, non-narrative films often employ collage-like cinematographic and editing techniques designed to call attention to themselves: defamiliarized camera angles, unfamiliar composition, obscure lighting, disjointed transitions, unexpected juxtapositions, and the like. Somewhat akin to lyric poetry, non-narrative films will often play with a central image, although other filmmakers will resist such unity. Other non-narrative films will focus more on repeated editing techniques or audio-visual patterns.

Non-narrative films draw from an array of styles and can incorporate found footage as well as original images and animation. Some non-narrative films will also be non-representational: movies that use abstraction and don’t reference objects from the external world. Instead, they might use colors and lines to create their effects.

While some non-narrative films lack sound altogether, others use music, ambient noise, and decontextualized words to complement or subvert their visual imagery.

Ballet mécanique (1924)

Bells of Atlantis (1952)

Let Your Light Shine (2013)

Characterization

Often times, the first “things” we notice in a film’s story are the characters. If we connect with characters, we like the film; if we are put off by the characters, sometimes we have a difficult time getting over those feelings to appreciate the storyline overall. The characters are truly our way in to what the filmmaker is trying to tell us. That said, there are some different methods of characterization–different ways we get to know said characters.

Characterization Through Appearance

Have you ever been told, “Don’t judge a book by its cover” when forming an opinion? Well, sometimes we have to admit that the first details we notice are often the outward appearance. How a filmmaker dresses a character causes us to react/respond to that character in a certain way. Jack Nicholson in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) enters our view in jeans, a leather jacket, and a stocking cap. He gives off rebel vibes from minute one, and we eventually learn that he is going to push the boundaries throughout the whole film, so our initial reaction to him is validated as the story plays out. Kate Winslet’s character of Clementine in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) has a unique look about her, with bold hair color choices that show us her personality is “outside the box.” She proceeds to have a profound influence on the other characters in the film as the story goes on, as we see others respond to her in much the same way we did from the beginning. Think about how characters look and the way they move on the screen as you develop your opinions about who they are.

Characterization Through Dialogue

Sometimes we need to not only hear what a character is saying, but we need to think about how they are saying it. Accents, regional dialects, speech patterns, pacing, sarcasm, word selection, grammar use–all of these choices that characters make in how they present themselves within the story can have an impact on what we think of them. These choices can tell us about their social standing, their personalities, and even give us a peek at how their minds work. Think about the difference between Sean Penn’s acting portrayal as the burn-out surfer dude Jeff Spicoli in Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982) and his moving portrayal of an intellectually disabled father, Sam Dawson, in I Am Sam (2001). The same actor transforms the way he speaks, and instantly affects how the audience responds to him.

Characterization Through Actions

Sometimes characters allow us to understand them better through the actions they take throughout the film. In fact, maybe the audience sees someone who initially looks off-putting and intense, and then because of some emotionally-charged actions they make within the storyline, the audience finds out they have more substance than we initially thought. Edward Scissorhands in the film of the same name is scary to look at, but his interactions with people from the neighborhood below his eerie-castle-like home show how big his heart is. His interactions would be examples of external actions that allow us to learn about who he is.

A filmmaker may also give insight into internal actions of the characters–those would be unspoken thoughts, fears…basically what’s going on inside a character’s mind. To allow the audience access to that information, filmmakers play with interesting visual and/or aural techniques to communicate that we are going inside of someone’s mind for information.

Characterization Through Reactions of Other Characters

Sometimes, as viewers, we need to pay attention to how other characters on the screen are interacting with and reacting to another character. Their faces and demeanor may change as soon as the character appears, and if we are astute with our observations, we can conclude things about the character from them and their reactions. If you look at the following clip from the end of Sunset Boulevard, you can see the looks on the faces of those who knew and loved the main character, Norma, well. Their showcased heartbreak at her dissolution gives the viewer a sense of sympathy for Norma that we might not otherwise have.

Sunset Boulevard (1950)

Characterization Through Contrast: Dramatic Foils

Filmmakers also may play with opposites to get us to understand each character better by how different they are from another character. We call those differences foils. Sometimes the contrast may be in physical stature or mannerisms. Other times, it might be a personality type or opinion. The old-school sitcom The Odd Couple showcased Felix Unger (always on time, neat and tidy, very put together) along with his roommate Oscar Madison (chronically late, messy as could be, and never caring about his appearance). Through the drastic contrast that was continually present on screen, the viewer could understand each character more and anticipate how he would react, given the distinctly different qualities they possessed. Another example could be Channing Tatum and Jonah Hill in 21 Jump Street (2012) Their physical characteristics are drastically different, and the strengths they bring to their police officer roles also set them apart from each other, while allowing them to complement each other in any given scene.

Characterization Through Caricature and Leitmotif

There are times when one feature of a character gets exaggerated to the point of us really only remembering that part of who they are–that characterization device is called caricature. Think about “Faceman” in The A-Team–he was known to be a womanizer, and that stigma influenced his entire character. Aside from a specific personality trait, caricature may also include how a person physically moves on screen (a limp, an exaggerated presence, etc.) and/or speech patterns of a character. When Janice (played by Maggie Wheeler) enters any scene in Friends, we know we are about to hear a thick New York accent, a whiny tone, and a laugh that sounds like machine-gun-fire. Those aspects of her character became the entirety of who she was. Then, if you add in the line “OH…MY…GAWD,” said in her perfectly slow-paced way, you also get a leitmotif for that character. A leitmotif is the repetition of a phrase or idea associated with a character, used so often that it becomes their trademark. Janice’s OMG line is expected almost any time you see her on screen. Clint Eastwood’s character of Dirty Harry, reappearing in multiple films, says “Go ahead…make my day,” and we immediately know he means business. These aspects of character development go beyond any other details and end up becoming the main focus any time the character is on screen.

Characterization Through Name

Lastly, think about how the name a character has might influence your reaction to them. Professor Snape sounds sinister from the get-go, and thus we don’t trust him early on in the Harry Potter storyline. Furthermore, consider both sound and meaning when looking at character names. In Good Will Hunting (1997) until we watch the film, we don’t know that the character’s name is actually Will Hunting. We see the character throughout the film search for the good in others because his life has been filled with a lot of people who didn’t show good will to him at all. There are double-meanings and positive connotations coming at us from the choice of name–we just have to be open to see them.

Varieties of Characters

The above methods of characterization influence our response to whomever is on the screen. We should also consider the varieties of characters, what purpose they serve, and what their development (or lack thereof) tells us about them. Here are some brief definitions:

Stock characters–characters included in the film because their presence is needed to create the realistic environment in which the story is taking place

Stereotypes–characters who fit into the pattern that we have come to understand of their type (the prom queen, the wise old man, the rich playboy who can’t settle down, etc.)

Static characters–characters who remain the same, no matter what happens in the film (unchanging)

Dynamic characters–characters who change because of what happens in the film (they grow, they learn, they understand themselves or the world differently because of what they’ve been through)

Flat characters–characters who are predictable, who lack complexity, and who are often representative of a whole group more than being individualistic

Round characters–characters who have unique and compelling qualities, who have a level of complexity that viewers are drawn into throughout the film, and who are considered three-dimensional

Irony

Another storytelling device to consider is irony. “Irony, in the most general sense, is a literary, dramatic, and cinematic technique involving the juxtaposition or linking of opposites. By emphasizing sharp and startling contrasts, reversals, and paradoxes, irony adds an intellectual dimension and achieves both comic and tragic effects at the same time. To be clearly understood, irony must be broken down into its various types and explained in terms of the contexts in which it appears” (Petrie and Boggs 67).

Dramatic Irony

This is a contrast between ignorance and knowledge. For example, the audience knows what’s about to happen in a horror film because they saw the “monster” run up the stairs, but now the character is going up those same stairs and doesn’t know who they are about to come face-to-face with. Such an example creates suspense in a horror film because we can almost see the demise coming. However, dramatic irony could also be used to humorous effect. In general terms, think about when we see something on the screen that the character doesn’t see–the contrast allows filmmakers to play with many types of responses.

Irony of Situation

This type of irony occurs when everything that was supposed to happen doesn’t, and instead there is a complete reversal or backfiring of events. The most famous version of this would be the plot line of Oedipus Rex. Characters hear a prophecy and do everything they can to keep it from coming true, and yet in spite of their efforts, the prophecy comes to fruition. Everything they try to avoid has the opposite effect.

Irony of Character

Think of this type of irony as dueling sides of a character. For example, Superman/Clark Kent–such a character is constantly battling both sides of who he is, and trying to appease both. It can also present itself in the form of a character who we anticipate to act one way in a given situation acting the complete opposite–for example, a strong, manly character ends up running scared from something/someone.

Irony of Setting

This ironic situation occurs when something happens in a place we don’t expect it to: a birth in a graveyard or a murder in a church. The effect tends to startle the viewer and catch them off guard.

Irony of Tone

This type of irony may be present in a couple different ways. At its most basic, we could consider it synonymous with verbal irony, aka sarcasm: for example, when a character is saying words that are sweet, but saying them with a sarcastic tone, and thus we know they don’t mean them in a sweet way. Or, the tone could be affected by using music to set us up for one thing and then providing us with something we didn’t expect. In the film Reservoir Dogs (1992), Mr. Blonde is about to cut off the ear of a man he’s holding captive. It’s a gruesome act, but the music playing in the background is “Stuck in the Middle with You” by Stealers Wheel; listen here for how upbeat it is…an odd contrast to the action in that scene:

“Stuck in the Middle with You” by Stealer’s Wheel

Cosmic Irony

This type of irony is the final one for us to consider. “Although irony is basically a means of expression, the continuous use of ironic techniques might indicate that the filmmaker holds a certain philosophical attitude or ironic worldview. Because irony pictures every situation as possessing two equal sides, or truths, that cancel each other out or at least work against each other, the overall effect of ironic expression is to show the ridiculous complexity and uncertainty of human experience. Life is seen as a continuous series of paradoxes and contradictions, characterized by ambiguities and discrepancies, and no truth is ever absolute. Such irony implies that life is a game in which the players are aware of the impossibility of winning and the absurdity of the game even while they continue to play. On the positive side, however, irony’s ability to make life seem both tragic and comic at the same moment keeps us from taking things too seriously or too literally.

Looked at on a cosmic scale, an ironic worldview implies the existence of some kind of supreme being or creator. Whether this supreme entity is called God, Fate, Destiny, or the Force makes little difference. The implication is that the supreme being manipulates events deliberately to frustrate and mock humankind and is entertained by what is essentially a perpetual cruel joke on the human race.

Although irony usually has a humorous effect, the humor of cosmic irony bites deep. It can bring a laugh but not of the usual kind. It will be not a belly laugh but a sudden outward gasp of air, almost a cough, that catches in the throat between the heart and mind. We laugh perhaps because it hurts too much to cry” (Petrie and Boggs 70).

A note about sources

This textbook reuses, revises, and remixes multiple OER texts according to their Creative Commons licensing. We indicate which text we are adapting with a footnote citation before and after each section of text. Additionally, we employ a number of non-OER sources. We indicate these using standard MLA citation. Full source information for both OER and non-OER sources appear in the works cited. Additionally, video clips link to their original source.

- https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/arts-ancillary/3/ ↵

- https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/arts-ancillary/3/ ↵

- https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/arts-ancillary/3/ ↵

- https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/arts-ancillary/3/ ↵

- https://uark.pressbooks.pub/movingpictures/chapter/narrative/#chapter-157-section-2 ↵

- https://uark.pressbooks.pub/movingpictures/chapter/narrative/#chapter-157-section-2 ↵

- https://docs.google.com/document/d/1KGdC_Oj0QA4d2B_SGrbaXUXd1LEnf_lvunW1V_nbkmI/edit#heading=h.5gitzrndih66 ↵

- https://docs.google.com/document/d/1KGdC_Oj0QA4d2B_SGrbaXUXd1LEnf_lvunW1V_nbkmI/edit#heading=h.5gitzrndih66 ↵

- https://uark.pressbooks.pub/movingpictures/chapter/narrative/#chapter-157-section-2 ↵

- https://uark.pressbooks.pub/movingpictures/chapter/narrative/#chapter-157-section-2 ↵

- https://ohiostate.pressbooks.pub/introfilm/chapter/narrative-2-structure-form/ ↵

- https://ohiostate.pressbooks.pub/introfilm/chapter/narrative-2-structure-form/ ↵

- https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/arts-ancillary/3/ ↵

- https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/arts-ancillary/3/ ↵

- https://milnepublishing.geneseo.edu/exploring-movie-construction-and-production/chapter/3-what-are-the-mechanics-of-story-and-plot/#:~:text=Outside%20of%20the%20characters%2C%20the,for%20the%20characters%20to%20grow. ↵

- https://milnepublishing.geneseo.edu/exploring-movie-construction-and-production/chapter/3-what-are-the-mechanics-of-story-and-plot/#:~:text=Outside%20of%20the%20characters%2C%20the,for%20the%20characters%20to%20grow ↵

- https://milnepublishing.geneseo.edu/exploring-movie-construction-and-production/chapter/3-what-are-the-mechanics-of-story-and-plot/ ↵

- https://milnepublishing.geneseo.edu/exploring-movie-construction-and-production/chapter/3-what-are-the-mechanics-of-story-and-plot/#:~:text=Outside%20of%20the%20characters%2C%20the,for%20the%20characters%20to%20grow. ↵