17 Writing about Film

One of the biggest pitfalls students face when writing about film is an overreliance on plot summary. While many assignments do call for an overview of a film’s plot, most ask students to do far more than rehearse a movie’s action. As you prepare to write, there are a number of steps that you can take to ensure that you understand how your instructor wants you to proceed.

What’s Your Purpose?

It’s imperative that you read your assignment closely. Without doing so, you may misunderstand the essay’s rhetorical purpose. Key words such as “analyze,” “respond,” “evaluate,” and “review” offer important clues about how to proceed even before you watch your film. Analysis, for instance, involves looking at a film’s or scene’s various components to see how they work together. A response, in contrast, calls for your overall impression of a film or scene. An evaluation requires a supported judgment: why does a film or scene succeed or not? A review is a particular type of evaluative assignment that asks for an overall impression, but reviews tend to be shorter and less academic than a formal evaluation.

Popular and Academic Writing Styles

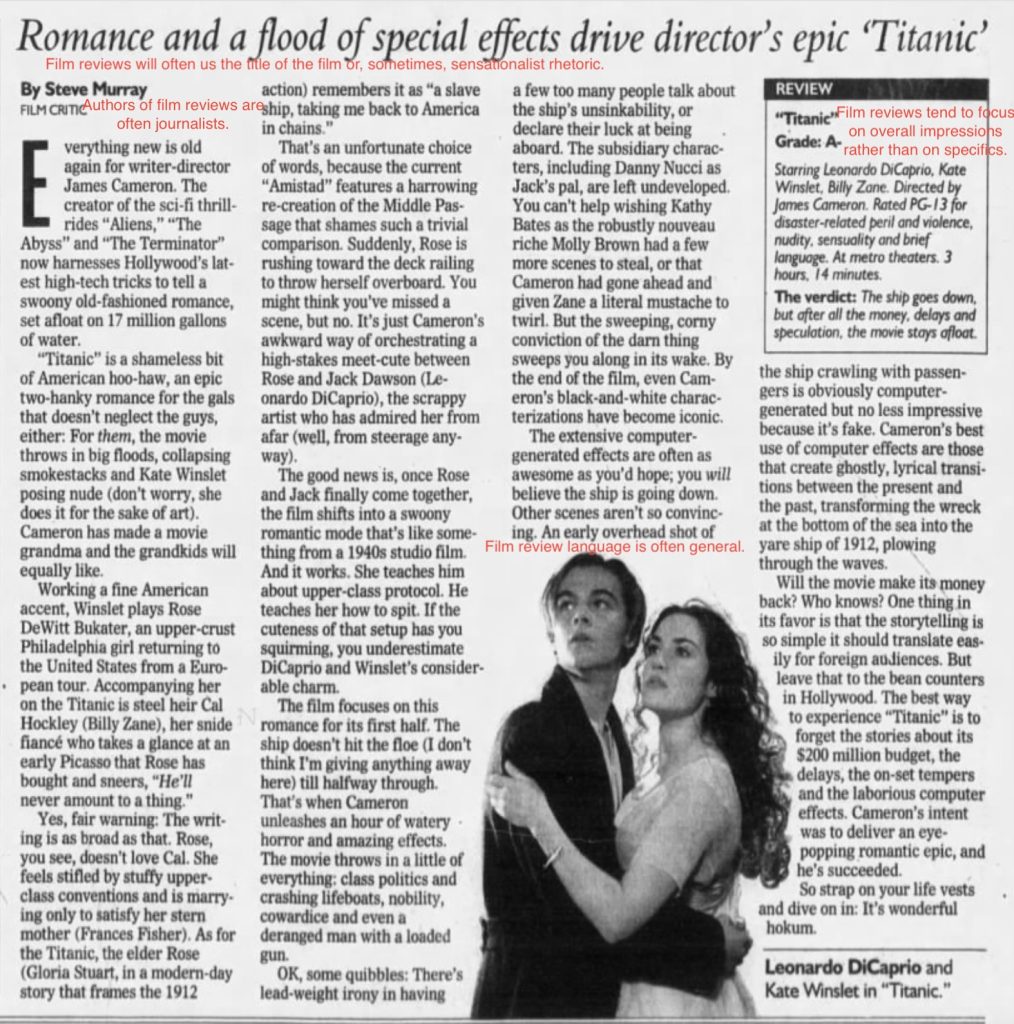

Film reviews are the most common type of popular writing on film. They typically appear close to a film’s release, and they are generally fairly short, sometimes less than a page but seldom longer than two or three pages. Film reviews may employ general cinematic language, but they nearly always strive for a verbal style that is accessible to non-experts. Usually, a review’s purpose is to recommend whether readers should see a movie or not. Most reviewers try to avoid spoilers, although they may give a general notion of the plot. In supporting their recommendations, reviewers will use explicit or implicit criteria (standards) that they will illustrate with a brief example or two. Reviewers are looking for the “big picture” and will rarely go into granular detail. For the most part, the argument in a review will lack the complexity required of an academic paper. On occasion, however, professors may ask students to write reviews that involve more nuance than that employed in most public reviews. Be sure to ask your instructor if you are not sure.

While some academic assignments about films can be short (such as a discussion post or brief response), they generally involve a more systematic, formal approach to writing than that used in popular reviews. Unlike the reviews published on websites and in popular periodicals, academic essays require far more preparation and reflection; after all, a film reviewer will likely only see a movie once before completing a review. This is not usually your film professor’s expectation. Given the complexity of many academic film assignments–which might, for instance, ask you to determine how a movie reinforces cultural stereotypes, how it reflects its era’s dominant ideology, or how its use of editing and lighting help establish its central themes–your instructor will often expect you to view a film (or a scene) multiple times. Academic writers on film, unlike movie reviewers, usually gear their essays toward readers with a degree of expertise (which includes your classmates, who have been exposed to film studies more than the typical layperson has.)

Additionally, formal academic assignments generally demand a much higher standard of evidence to support a claim. While a film reviewer might use a single example to prove a point, a student writing academic film criticism may need to show a pattern of evidence in order to convince the audience. An academic assignment, moreover, may call on you to focus on a single aspect of a movie–such as its cinematography, ambient sound, or acting–rather than on the whole. Further, depending on the type of academic assignment, your instructor may require you to incorporate highly technical language into your essay: words and phrases that the average person may not be familiar with such as mise-en-scène, diegetic, and eyeline match. Some types of academic assignments call on students to engage with a film’s context–the socio-economic and ideological circumstances surrounding its creation or reception, for but one example. Since academic authors assume that their audience has viewed (perhaps dozens of times) the film under consideration, their essays will use spoilers. Unlike film reviewers, academic film critics tend to adopt an objective tone in their work, although such “neutrality” is not universal. Some types of academic film assignments will require students to conduct research and include a bibliography as well.

The video below examines how film studies differs from popular approaches to film.

Zachary Xavier on film studies

Before You Write

As indicated above, make sure to review your assignment multiple times and ask your instructor for clarification if needed. Once you have a grasp on the nature of your topic, you will need to watch and rewatch your film(s.) The first time they view a film, most spectators focus mainly on plot. Even if we notice some interesting editing or sound effects along the way, most of us are simply trying to understand what is happening at the level of action. Because of this, additional viewings are necessary so that we may pay closer attention to specific aspects of a movie. Indeed, some academic writers will watch a film or scene with the sound off so they can focus better on editing or turn their backs to the screen so they might turn their entire attention to sound. It’s important to limit distractions as much as you can. Avoid multitasking and use headphones if people or sounds are liable to interrupt your concentration.

When you watch your film the second (third, etc.) time, make sure to take copious notes. Pause the film as needed so that you can describe what you see or hear in detail should you find it pertinent. Remember that a single frame of a film may contain multiple noteworthy elements. Karen Gocsik reminds us to “be alert to things about the film that strike [us] as different, memorable, or puzzling at the moment of viewing” (24). She further asserts that “taking note of these things, and framing [our] notes about them in the form of questions, will prompt [us] during [our] viewing(s) to return to those moments to see if [we] can answer that question” (24).

After completing your notes, look for patterns and highlight significant example shots, scenes, and sequences.

Because writing is an iterative process, you may need to return to your film or research multiple times and take subsequent notes. Relying on memory of a single screening can lead to imprecise writing. This is especially true if you are not sure of your topic in advance.

Choosing a Subject

If our instructor does not supply us with a topic, we can use our notes and questions to come up with some of our own.[1] In the field of film there are multiple subjects that people might consider. Obvious topics are actors and good performances or moments that are crescendos. Here are some popular topics that can help generate effective essays.

- How effective is the use of a group of actors to create an ensemble?

- How are the scenes and sequences of a film structured to reinforce the key themes?

- How does the film deal with difference in gender, race, disability, or social background?

- How do such structural choices increase or decrease a film’s impact?

- How does such structural choice affect a film’s reception?

- How does a film construct reality?

- How do films like Being the Ricardos (2021) question and shape what we know about famous people like Lucille Ball?

- How does a film like Star Wars (1977) deal with issues of family?

- How does a series like Star Wars establish patterns that are used across the movies in its cinematic universe?

- How do films use sound to manipulate audience response?

- How does editing contribute to a film’s meaning?

- How does a film conform to or deviate from genre conventions?

These are only a few subjects that one could explore, but finding a subject that is less obvious and reveals depth to a film can be useful.

Thesis

As with most academic papers, essays on film generally require a thesis. A thesis is usually a strongly prepared idea that has a narrow subject, a clear, defensible position, and some preview of where the essay will go. A thesis should offer readers more than a general observation. For example saying that Citizen Kane (1941) is a great film (or an overrated or boring one) fails to give readers insight about why we should believe that. Similarly, stating that Citizen Kane is an influential film is simply a fact.[2] Effective thesis statements will attempt to answer an interpretive question (such as whether the film values style over substance) or illuminate some area of the film that a viewer might not have noticed (such as the film’s use of deep focus to underscore Kane’s alienation). Ultimately, reasonable people should be able to disagree with a thesis. If they can’t, then you don’t truly have an arguable subject.

A thesis should also aim for precision and offer some suggestion of the reasoning behind the argument or why the point is important. A vague thesis such as “Citizen Kane uses deep focus to show Kane is alienated” doesn’t reveal enough of either the rationale for the position or why such an observation is significant in the first place. In contrast, “Citizen Kane employs deep focus in key scenes to compare the emptiness of Kane’s life to his cavernous mansion” helps orient readers to the scope and importance of the argument.

Writers will typically place the thesis toward the end of the introduction.

Topic Sentences

While the thesis offers the essay’s overall argument, the body paragraphs will divide that argument into key components. Usually, these subtopics will consist of supporting reasons for the author’s position. Just as in other forms of writing, film essays should limit each body paragraph to a single idea. A body paragraph will typically include a topic sentence near the beginning. The topic sentence should demonstrates the relationship of the subtopic to the thesis. If the thesis involves the importance of domestic space in Moonlight (2016), for example, a body paragraph might include a topic sentence that focuses on how Chiron views Juan and Teresa’s house as a place of refuge.

As with the thesis, the topic sentence should be specific, and it should reflect a rationale. A weak topic sentence, such as “Juan and Teresa’s house is a place of refuge,” does not provide the paper’s audience with a sense of why this is so. Conversely, a sentence such as “With its airy and light domestic space and table full of comfort food, Juan and Teresa’s house offers Chiron a place of refuge from his dimly lit, rage-filled apartment” gives readers a clear reason for the position while also reminding them of the essay’s overall argument.

Unless your instructor requires it, a paper will not have a set number of supporting reasons, and a complex point may need more than one body paragraph to make.

Evidence

Just like in other types of papers, academic film essays require some sort of support for their points. Depending on the type of assignment you have, the evidence will tend to fall into the following categories:

- descriptions, analyses, or evaluations of shots or scenes from the film

- film stills or clips

- information from sources (e.g., an excerpt from a journal article on the film, its cultural background, or its historical era)

- personal experience with the topic (e.g., you are a part of the community depicted in the film)

The amount of evidence use will depend on the type of assignment and on the complexity of your point. A short response paper, for example, may not need as much evidence as a lengthy semiotic analysis. Similarly, a point that a reader should grasp quickly (such as the type of music used in a scene) won’t usually necessitate as much evidence as a point that requires you to demonstrate a pattern (such as a film’s negative representation of women.) In cases where readers should not reasonably resist your point, giving example after example might irritate them, whereas not providing enough evidence to support a complex–and potentially controversial–idea may frustrate the audience.

Also, it is imperative not simply to drop a reference to a scene or insert a statement from a source without providing commentary. Sometimes, we might think something is “obvious,” but others may not (literally) see it the same way. Instead, explain the significance of your example and show how it illustrates your broader point. As you comment on your evidence, many instructors will require you to use film vocabulary that demonstrates your understanding of key cinematic concepts.

In arranging your paragraphs, an effective general pattern involves TED: topic, example/evidence, discussion. In more complex situations requiring more evidence, you may need to use TEDED or even TEDEDED (and so on.) Generally, the discussion portion of the body paragraph will be the lengthiest.

Additionally, using a film still or video clip can quickly illustrate a point that a verbal description might take dozens of words to make.

The following video provides effective steps for moving from a topic sentence to an example to discussion of that example. Please note that it only shows the general structure and does not offer a fleshed-out paragraph.

Ignite on Analyzing Film

Here’s another video that discusses the general process for writing about film.

iitutor.com’s Writing about Films Made Easy

Sources

When writing about film in an academic way, it is imperative to have good sources that can help you.[3] Indeed, sometimes you might seek sources first and construct the thesis and subject around sources you can find as you respond to a common issue connected with your film. The first place to find effective sources is not IMDB or Wikipedia, though. Those are general sources that can help orient readers about broad issues but that lack the type of nuance typical of an academic source. They often don’t provide specific evidence, they are usually not written by scholars, they are often unsigned and anonymous, they frequently don’t use sources, they often present unsubstantiated opinion, they were not always edited or verified by an expert, and they might describe or contain information that is either false or misleading.[4]

A Google search can yield quality academic sources, of course, but it is important to evaluate your “hits” systematically using a method such as the CRAAP test.

Web sources vary widely in quality, and while some essays and blogs may be written by expert scholars, others may be composed by weak writers and thinkers. Online sources range from academic film journals such as Senses of Cinema and CINEJ Cinema Journal to the vague ramblings of an anonymous troll and everything in between. If you are looking for film reviews, there is no better repository than the public Web. Rotten Tomatoes is a popular review aggregator, but for most academic papers make sure to focus on the critics’ reviews rather than those of the audience. The MRQE site is another excellent search engine devoted to film reviews.

For academic sources on film, though, your library offers the gold standard. Of course, the library site will enable you to look up physical books, and the library’s interlibrary loan system can help you access film books and periodicals that are not housed at ICC. The library’s many databases give you access to thousands of full-text articles, and the aforementioned interlibrary loan system can locate even more. The library has a host of tutorials that can help you navigate the various systems.

Databases where you may find ebooks on film include Academic Complete on Ebook Central and Ebsco Ebook Collection. You may locate articles on cinema on many databases, including Academic Search Complete, ProQuest One Academic, JSTOR, Academic OneFile, Humanities International Complete, and the MLA International Bibliography.

When searching for articles, be sure to use the “peer review” or “scholarly” filter in order to eliminate general references from newspapers and similar sources. Additionally, changing the search parameters from “all” to “title” can help produce more targeted results, as this option will not yield casual references to your film. If you are pressed for time, you should also click on “full text,” but as mentioned above if you allot yourself enough time the library will be able to order articles that aren’t full text. If you are researching a very famous older film, you may also want to use the date filter so that you can locate the most recent sources on your topic.

As many scholarly articles are quite lengthy, we advise you to read the article’s abstract, a one- or two-paragraph summary of the source’s contents.

Distinguishing Peer-reviewed Academic Film Criticism from Film Reviews

Academic film criticism, sometimes called scholarly or peer-reviewed film criticism, is much more rigorously screened than other types of sources on film. These articles are written by scholars in the field and are reviewed by at least two other experts before being accepted for publication in an academic journal. Peer reviewers examine a host of factors, including methodology, originality, comprehensiveness, logic, evidence, writing, and quality.

Peer-reviewed sources on film vary widely, but they share a number of traits, including systematic citation of references, use of specialized jargon, relatively objective/neutral tone (exceptions exist), comprehensive level of detail, and narrow focus. They often lack visual appeal, although they may include film stills (usually black and white).

Sample page from an academic journal article on cinema

This lecture from Amy Chambers on writing about film provides some helpful tips for writing academic (and popular) criticism on film.

While some academic journals on cinema include film reviews, most do not. Film reviews appear in diverse array of places, including newspapers, magazines, websites, blogs, and video sites such as YouTube. This type of source may be appropriate for certain types of academic papers, but some instructors will prohibit their use for some assignments. Be especially careful with blogs and websites not associated with an organization or print periodical.

Film reviews typically will have little peer-review process (perhaps limited to appraisal from a non-specialist editor), and many have no peer-review process at all. Such sources often have a financial imperative and seek to entertain or inform a broad swath of readers.

Film reviews usually forego jargon, although they may use some common cinematic vocabulary. They also rarely use sources. Tone can vary widely, from “objective” to extremely subjective/personal. Usually, film reviews are geared toward an overall assessment and are written after a single viewing of a new release. Some blogs and video channels may review classic films long after their initial release, however.

Sample film review

A.O. Scott on writing film reviews

A note about sources

- https://docs.google.com/document/d/14iGxxNB0Js2jEdd8I-QxgwyO79iVzvKK/edit#heading=h.39kk8xu ↵

- https://docs.google.com/document/d/14iGxxNB0Js2jEdd8I-QxgwyO79iVzvKK/edit#heading=h.39kk8xu ↵

- https://docs.google.com/document/d/14iGxxNB0Js2jEdd8I-QxgwyO79iVzvKK/edit#heading=h.39kk8xu ↵

- https://docs.google.com/document/d/14iGxxNB0Js2jEdd8I-QxgwyO79iVzvKK/edit#heading=h.39kk8xu ↵