15 Adaptations

In the earliest days of cinema, audiences were wowed by short, non-fiction films of people walking, trains moving, and walls being demolished. Such actualités found popularity with audiences eager to witness the novelty of a new technology, and they were the dominant mode of film from the late 1880s to about 1907.

Even as actualités thrilled working- and middle-class spectators, though, directors such as Alice Guy, Georges Méliès, and Edwin Porter were experimenting with narrative films. These fiction films quickly dominated the market, and filmmakers needed to find new content to keep up with demand. Because of the cost involved in film production, literary works offered a quick way to provide audiences with content that had already been vetted. They also allowed the fledgling medium to reveal its artistic pretensions by adapting universally acclaimed works, such as those by Shakespeare, Dickens, or Sophocles. Additionally, adaptation theorist Deborah Cartwell points out that in the silent era adapting a well-known story made it easier for audiences to follow complicated plots (2).

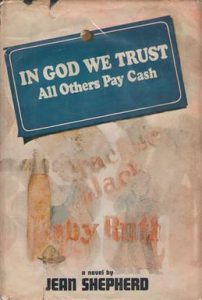

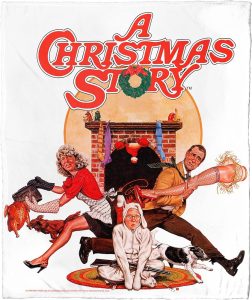

As fiction films exploded in popularity, so did the number of adaptations. Even today, roughly half of all films produced stem from pre-published sources. Sometimes, these sources are extremely familiar and popular, as in the case of The Hunger Games or the Marvel Universe. In many cases, though, most audience members will be quite unfamiliar with a film’s source material, as with, for example, Oppenheimer (2023, adapted from American Prometheus) or A Christmas Story (1983, adapted from In God We Trust: All Others Pay Cash, 1966.)

In God We Trust: All Others Pay Cash/A Christmas Story

In addition to drawing from obvious sources such as novels, plays, and short stories, films have been adapted from a diverse group of texts including poetry, video games, comic books, board games, court transcripts, radio shows, popular music, theme park rides, diaries/memoirs, and even toys.

What Is an Adaptation?

What, however, do we mean when we refer to a film as an adaptation? Linda Hutcheon provides a multi-part answer to the question:

- An adaptation “is an announced and extensive transposition of a particular work or works.”

- An adaptation “always involves both (re-)interpretation and then (re-)creation.”

- An adaptation “is a form of intertextuality: we experience adaptations … as palimpsests through our memory of other works.” (7-8).

Implicit in Hutcheon’s definition are the competing notions of similarity and difference (transposition, reinterpretation, recreation, palimpsest, memory.) While we may recognize an adaptation’s source text, films are fundamentally different than novels and other media. Despite such core distinctions, however, adaptations will often frustrate spectators familiar with the original. This discontent will often manifest in decidedly moralistic ways.

Linda Hutcheon on adaptation

Fidelity Criticism

Fidelity criticism, the most common–and naïve–way to evaluate an adaptation, assumes that any significant deviation from the source text constitutes a “betrayal” of the original. People using fidelity criticism to critique adaptations will employ language charged with indignation: “betrayal,” “unfaithful,” “violating the spirit,” “inexcusable,” “desecration,” “vulgarization.” Epitomizing the base assumption of such a view is the phrase “the book is always better,” which presupposes an artistic hierarchy that places literature above film. Thomas Leitch, an adaptation theorist, points out the absurdity of this sentiment: “no matter how clever or audacious an adaptation is, the book will always be better than any adaptation because it is always better at being itself … this reductio ad absurdum … indicates just how trivial a claim we make when we argue the book is better” (16).

As mentioned above, however, audiences will often watch and enjoy an adaptation without even knowing that the film drew inspiration from another work. Would reading the source after learning that a film was based on a book erase the initial enjoyment of a movie? It’s possible, but we tend to doubt it. Rather, the initial response underscores a key motivator for fidelity criticism: a sense of protectiveness.

Usually, reading is an intimate, personal experience in which our imaginations bring the author’s words to life. In some cases, we identify so strongly with a story’s world and its characters that we read the work over and over. Sometimes such books shape our “real life” actions and language, and we may even wear costumes to attend events devoted to our favorite fictional character.

There’s little wonder, then, that when we see someone else’s imagination projected on the screen and that film deviates sharply from our personal vision–perhaps through the deletion of our favorite subplot or the addition of dialogue not found in the book–that we bristle. The more famous the work, the more likely a film will face extreme scrutiny. A film based on a less popular source will certainly receive criticism from those who read the original work, but it is far less likely that the critical consensus of the film will employ moralistic rhetoric. Millions of people read Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone before watching the 2001 adaptation, but very few viewers of the highly popular Die Hard (1988) knew that it was based on the novel Nothing Lasts Forever (1979) let alone had read the book. Ironically, some critics faulted the former film for sticking too closely to J.K. Rowling’s novel and not taking any risks!

Differences between Die Hard and Nothing Lasts Forever

Consequently, many adaptation scholars avoid judging movies with a fidelity model. Instead, they attempt to evaluate a film on its own merits and with criteria more conducive to explaining a multi-track medium.

Multi-Track Criticism

Robert Stam provides a helpful alternative to fidelity criticism with his concept of multi-track media. Stam observes that a written text like a story or novel is a single-track medium that conveys meaning primarily, if not solely, verbally. In contrast, film uses multiple tracks, such as visuals (both moving and still), sound (score, ambient, soundtrack), and language (written and oral.) Because of film’s multi-track capabilities, therefore, Stam argues that fidelity is “literally impossible” and that a “filmic adaptation is automatically different” (17). As we’ve seen in Chapter 11, a single page (or sentence!) of a screenplay might play out over several minutes, while whole pages might constitute only a few seconds of screen time.

Filmmakers, then, necessarily change a single-track text into multiple tracks. Because of this, when we analyze an adaptation we must attend not only to the dialogue and plot, but also to the many elements–such as editing, cinematography, color, and acting–that we’ve discussed throughout the previous chapters. Additionally, even common elements of fiction–such as first-person perspective or exposition–often are difficult to employ on film without striking a false note with the audience. Similarly, basic elements of film–such as sound, lighting, and camera angles–are notably absent from written works (not to mention toys like Transformers and Barbie or Disney rides such as the Pirates of the Caribbean and Jungle Cruise.)

Comparison of Pirates of the Caribbean film and ride

Employing a multi-track approach necessitates a sensitivity to intertextuality, which M.H. Abrams defines as “the multiple ways in which [a] text is in fact made up of other texts, by means of its open or covert citations and allusions, its repetitions and transformations of the formal and substantive features of earlier texts” (398). In other words, intertextuality involves a reciprocity between works. Our understanding of a film adaptation can affect our comprehension of its source(s) just as the reverse can be true. As Stam observes, “every text, and every adaptation, ‘points’ in many directions, back, forward, and sideways” (27). Holding this in mind, we can discuss an adaptation in terms of its source material, but we can also examine it through other lenses, such as cinematic conventions and socio-cultural perspectives.

Equivalencies

When we do decide to compare a film adaptation to a source, it can be helpful to examine how the movie employs visual, audio, and formal strategies that correspond (or not) with the original text(s.) In doing so, try to reserve judgment at first about whether the equivalence is “better” or “worse” than the strategies used in the original text. Instead, focus on the question “why”: why did the screenwriter, director, cinematographer, actor (etc.) decide to interpret a scene in this way? Was this a risky, curious, or obvious choice? Were these choices simply practical (as in the decision to condense a twenty-page description of a character’s appearance to a three-second close-up of the character’s face)? Were the choices interpretive (such as Baz Luhrmann’s decision to use hip-hop in his 2013 version of The Great Gatsby)? Why might have the filmmakers opted for this choice? Why has a filmmaker (roughly) kept the same information, added scenes, or cut scenes? Asking “why” will help us explain decisions to cut our favorite side character, subplot, or speech from the film. Remember that most films don’t exceed two or two-and-a-half hours, which means that by necessity they won’t be able to engage with everything in a five- or six-hundred-page novel.

John M. Desmond and Peter Hawkes encourage viewers to answer the “why” question by proposing a reason for the alterations they notice. “Filmmaking is deliberate, not accidental,” they assert, “and changes can indicate an adapter’s practical considerations in making the film, his or her interpretive insights into the literary text, or outside factors” (51).

Concision and Expansion

Even when adaptations retain the general plot of its source, they make wide use of concision and expansion. Concision involves shortening a scene, whereas expansion lengthens a scene. Filmmakers will often use these practices to emphasize or deemphasize a particular interpretation of a scene, establish a rhythm, or create a mood. At other times, though, they may need to employ concision or expansion because of practical considerations such as trying to mask a weak performance or attempting to highlight a cameo by a famous actor. In the case of long novels, filmmakers will lean heavily on concision, while short stories may prompt writers and directors to “fill in” the gaps with expansion.

Close, Intermediate, and Loose Adaptations

In making our comparisons, we can also reach an assessment of the adaptation’s overall association to its source. Desmond and Hawkes categorize such relationships as either close, intermediate, or loose. They define the terms as follows:

- A close adaptation is when “most of the narrative elements in the literary text are kept in the film, few elements are dropped, and not many elements are added.”

- An intermediate adaptation is when “some elements of the story are kept in the film, other elements are dropped, and still more elements are added.”

- A loose adaptation is when “most of the story elements in the literary text are dropped from the film and most elements in the film are substituted or added.” (44)

We should caution that while noting whether film’s take on its source is close, intermediate, or loose is an effective way to categorize adaptations, such correspondences do not automatically determine whether a film is successful or not. For instance, Francis Ford Coppola’s widely acclaimed Apocalypse Now (1979) preserves some archetypal elements from its source (Joseph Conrad’s The Heart of Darkness), such as the journey up river and the corruption of Kurtz, but the film at best qualifies as an intermediate adaptation and most would consider it a loose one.

Comparison of Apocalypse Now and Heart of Darkness

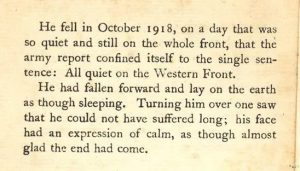

A more recent example of an acclaimed film that changes its literary source in key ways is All Quiet on the Western Front (2022.) An earlier version of the film from 1930 maintained a much closer relationship with the source text, but the 2022 film received many accolades for its cinematography and anti-war message. Despite deviating in key ways from the book’s plot–perhaps most noticeably in the ending–the film powerfully updated the material for a contemporary audience. Below, compare the novel’s final paragraphs with the ending of both the original ande new film versions and consider why the later director decided to alter the scene. Notice, though, that even in the closer original adaptation, the director included material that did not exist in the original.

Ending of All Quiet on the Western Front (1930)

Ending of All Quiet on the Western Front (2022)

Point of View

Perspective poses a special problem when discussing adaptations. While some experimental films attempt to use the first-person point of view consistently throughout their running length, most films inevitably revert to the third-person perspective. While directors may incorporate voiceovers, or subjective camera positions, they recognize that audiences will quickly tire of both methods. Look, for instance, at the following clip from a 1947 adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s The Lady in the Lake:

The Lady in the Lake

The effect is disorienting, to say the least. Audiences are conditioned to see the protagonist on screen, but a true first-person perspective subverts that expectation and can become distracting.

Because of the “artificiality” of such subjective techniques, directors will more often pair a voiceover with a visual of the action being described. Unfortunately, while we understand that the voice is setting up a subjective position, the visuals usually undercut the effect after a few minutes (or even seconds) as the camera switches angles and we see the speaker from the more typical third-person point of view.

Look at the following clip from Sofia Coppola’s 1999 adaptation of Jeffrey Eugenides’s The Virgin Suicides, for instance. The novel uses an unusual first-person plural (“we”) narrator that recalls events that took place decades prior. Even though the film acknowledges this, employs graphics to signal the past, and uses “we,” the camera invariably focuses on the action in a way that privileges the present (the novel’s extended memories) and the third-person.