11 Screenplay

What Is a Screenplay?

[1] This may seem like an obvious question, especially if you are already somewhat familiar with how movies are made. A screenplay is the written story created in the early development phase of a film project. It’s the document that is used to get producers, directors, actors and financiers onboard so the movie can be greenlit.

Once the movie is financed, the film moves from development to the preproduction phase, and now the script (now sometimes called a “shooting script”) becomes a map or guide for the crew as to how the movie should be made. At this point, the director and other key creatives, such as the production designer and cinematographer, will have a hand in crafting the movie and some changes will most likely be made to the script. The writer will typically get to do at least one rewrite on the project and may even stay on through the entire production of the film to make last minute changes to the script.[2]

Below, Studiobinder summarizes the importance of screenplays to a film’s success.

Anatomy of a screenplay

The screenplay, or script, in cinema is many things at once.[3] Though rarely meant to be read as literature, it is a literary genre unto itself, with its own unique form, conventions, and poetic economy. It is also often a sales pitch, at least in the early stages of production, the best version of the idea, on paper, to attract collaborators and, ultimately, the capital required to make a motion picture. First and foremost, the screenplay is a technical document, a kind of blueprint for the finished film.

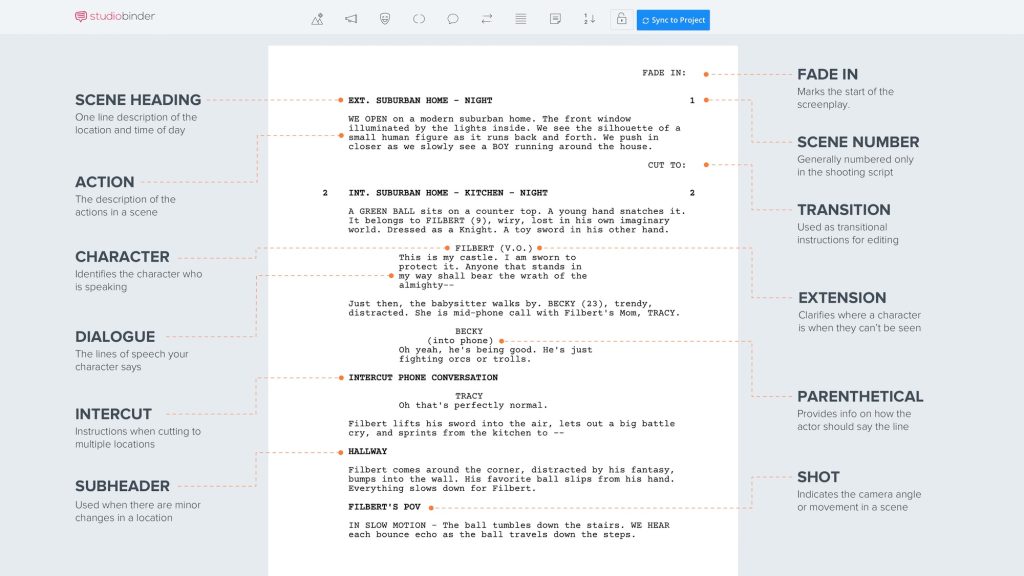

Ever seen a screenplay? Let’s take a look at what one looks like:

Annotated page from screenplay

Every element of the script page is there for a reason and helps everyone on the creative team stay on the same page. Literally. The scene heading, for example, lets everyone know at a quick glance if that particular scene is set inside or outside, INT or EXT, where, exactly, they are supposed to be, and what time of day it is. That information, of course, will affect every member of the crew, from the producers and assistant director responsible for scheduling, to the camera crew responsible for lighting the scene, to the production designer responsible for the look of the location, to the transportation crew responsible for getting everyone there safely.

Notice, too, how economical the writing must be. There is no room to probe the inner life of characters or spin off into detailed descriptions of the space. That is one of the most important aspects of great screenwriting: the economy of language. Imagine you’re watching a film or tv show and your roommate is in the other room making a nice medium rare New York strip and a mushroom risotto. They don’t want to miss anything, so you have to describe in detail everything you’re seeing and hearing by yelling across the apartment. What do you include? What do you leave out? Obviously you want to include what characters are saying, but beyond that, probably just the essentials. In fact, as a general rule of thumb, every page of script should equal about a minute of screen time. That doesn’t always work out exactly, but it does tend to average out over the length of the screenplay. So there simply isn’t time to include anything but the essentials and allow the other creative collaborators on the team the freedom to interpret the rest.[4]

Characteristics of a Screenplay

While they can vary widely, successful screenplays share many traits in common.

The three-act structure that we discussed in Chapter Three is one standard features of a screenplay. You’ll recall that the first act functions as the set-up, the second serves as the rising action, and the third offers the resolution. Generally, screenplays will devote about a quarter of their space to the first act, half to the second, and another quarter to the third. This structure lends itself well to pacing that keeps the audience engaged. Obviously, many directors, such as Chantal Akerman, Quentin Tarantino, and Christopher Nolan, subvert the expectations that come with classic structure. Other popular screenplay structures include multiple timelines (Everything, Everywhere, All at Once [2022], for example), parallel stories (such as in Shortcuts, 1993), reverse chronology (e.g., Betrayal, 1983), the Rashomon Effect (telling the same story from different views as in, obviously, Rashomon [1950]), and real-time (like Run Lola Run, 1998.)

Studiobinder on screenplay structure

Themes or main ideas will serve as the core of most screenplays. Although some screenplays will rely heavily on generalized ideas such as “good versus evil” or “coming of age,” many screenwriters aspire to generate more singular takes on recognizable situations. Such an approach will provide more emotional touchstones for the audience, and it will also help to unify the narrative. Experienced screenwriters will avoid “tacking on” a “message” and will instead incorporate their ideas into multiple areas of the screenplay, from plot, character, and dialogue to audio-visual imagery, mood, and setting. Additionally, stronger screenplays typically avoid themes that don’t allow for multiple interpretations.

Billy Mernit on theme in screenplays

Another key aspect of a good screenplay involves character development. A screenplay needs to convey clear motivations for its main characters. While some screenplays may rely heavily on archetypes like the “mad scientist” or “final girl,” most successful modern movies aim for more nuanced characters that transcend their type. Consequently, screenwriters will often create elaborate backstories for their characters even if those details don’t make the final cut. Writers will also plot out a development arc for their key figures wherein the audience witnesses how various struggles transform characters for better or worse.

Ken Atchity on character development

Dialogue, of course, is central to understanding characters and their actions. Successful screenplays employ dialogue that seems natural, geographically specific, and well-suited to individual characters. Stilted dialogue, overly clever dialogue, or dialogue in which characters sound interchangeable will readily burst a film’s illusion of reality, while distinctive, image-rich dialogue that contains significant subtext will hold the audience’s attention. Professional screenwriters also recognize the importance of pauses, changes in tone, rhythm, interruptions, characters “talking over” one another, syntax, and other elements that add to a conversation’s sense of authenticity. Good screenplays will also avoid “exposition dumps” in which characters explain actions or backstories at length. As a general rule, screenplays should show rather than tell and rely on audio-visual storytelling more so than on words. Indeed, many screenwriters advocate a “less is more” approach to dialogue.

Now You See It on film dialogue

Another important element of a screenplay involves setting, a concept we discussed in Chapter Four. A relevant concept from science fiction, world building, is instructive here. World building refers to a screenplay’s attempt to develop a detailed, coherent, and unique setting. Such settings tend to address numerous variables ranging from geography, dialect, and climate to socio-political dynamics, religion, and art. Screenplays need to at least hint at factors that will influence how characters will engage with their environment. What kind of technologies, historical/current events, and economic systems will characters encounter or use, for example? Believable answers to such questions will help create believable plots and characters, what poet Marianne Moore described as “imaginary gardens with real toads in them.”

Karel Segers on world building

How Do Filmed Scenes Differ from Their Screenplays?

John August created a great video that compares the screenplay from Whiplash (2014) to what appears on the screen. Notice that while many of the changes are minor (such as altering “amazing” to “great” in the dialogue), some revisions are fairly substantive (a huge section is deleted around the 3:41 mark, for instance.)

Whiplash

Page from Animal (2020) screenplay.

Now here’s the scene as it was shot and edited from that screenplay:

Animal

First, notice the clip is about one minute, equal to that one page of screenplay. Second, how does the script page compare to the finished scene? What do you notice in the script that isn’t on the screen? What do you notice about the finished film that isn’t in the script? You’ll likely notice that there is no mention in the screenplay about how the camera moves or how it frames the image. Nor do you notice anything about the music, or the boy’s wardrobe, or that dog in the background, or the fact that it’s raining. You might notice mention of an alarm clock that doesn’t show up on screen.

There are any number of reasons for some of the differences. Some of them are intentional. How the camera moves is the cinematographer’s job, not the screenwriter’s. Likewise, the boy’s wardrobe is the concern of the production designer and wardrobe department (though the script does mention the woman’s robe because that is important to the narrative, and that is the screenwriter’s job). Some of the differences, though, are due to the realities of production. Just like a blueprint is a plan for a building, the screenplay is a plan for a motion picture. Once you start building it, you have to confront and overcome hundreds, maybe thousands of variables you could not anticipate. Maybe the weather turns on the last day of filming and you’ve got to incorporate a thunderstorm into the story. Maybe a neighbor is out walking the dog and ends up in a shot, so you have to layer in a dog barking in the sound design and carry that over to the next scene.Maybe once you’re in postproduction and while the editors are putting the pieces together, they realize that last line would work much better over the next scene. What about that alarm clock? Maybe the director decided that it was too cliché once they were on the set and wanted to try something different with the actor. According to Russell Leigh Sharman, who wrote, directed, and edited Animal, all of the above are true!

The most important thing to remember is that cinema is a collaborative medium. There’s always a give and take between the script and the finished film, just like there is between the director and the screenwriter, cinematographer, production designer, sound designer, actors, editor, etc. As much as a screenplay can and should be a great read, it is, ultimately, a technical document, a plan for something exponentially more complex.[6]

A note about sources

- https://docs.google.com/document/d/1KGdC_Oj0QA4d2B_SGrbaXUXd1LEnf_lvunW1V_nbkmI/edit#heading=h.etqsmihd39ne ↵

- https://docs.google.com/document/d/1KGdC_Oj0QA4d2B_SGrbaXUXd1LEnf_lvunW1V_nbkmI/edit#heading=h.etqsmihd39ne ↵

- https://uark.pressbooks.pub/movingpictures/chapter/narrative/#chapter-157-section-1 ↵

- https://uark.pressbooks.pub/movingpictures/chapter/narrative/#chapter-157-section-1 ↵

- https://uark.pressbooks.pub/movingpictures/chapter/narrative/#chapter-157-section-1 ↵

- https://uark.pressbooks.pub/movingpictures/chapter/narrative/#chapter-157-section-1 ↵